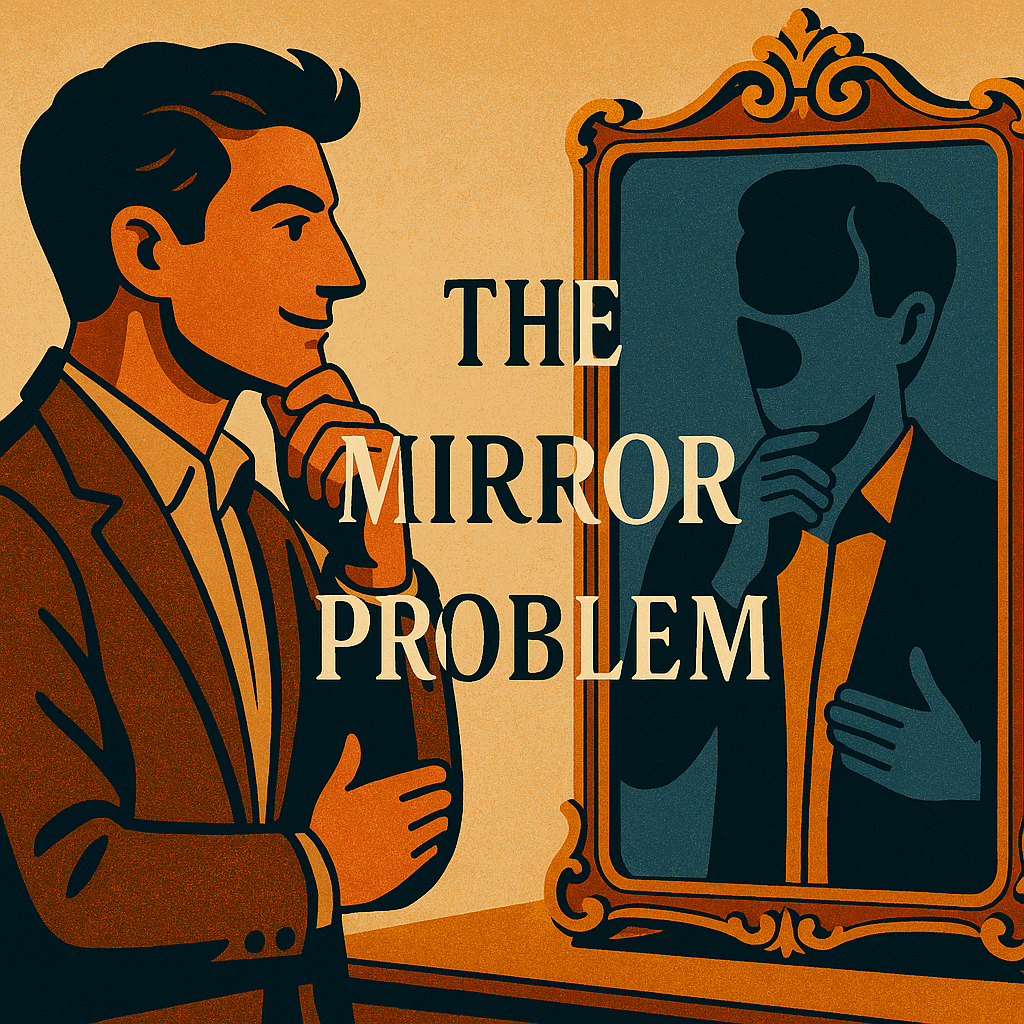

The Mirror Problem

Why we can't see our own blind spots (and what to do about it)

"It is the obvious which is so difficult to see most of the time. People say 'It's as plain as the nose on your face.' But how much of the nose on your face can you see, unless someone holds a mirror up to you?" — Isaac Asimov

The Anatomy of Invisible Obviousness

Your nose is the most prominent feature on your face, impossible for others to miss, yet completely invisible to you without assistance. This isn't a design flaw—it's a perfect metaphor for the most critical problem in human awareness: we are systematically blind to the very things that define us most clearly.

The mirror problem goes far deeper than physical features. We can't see our own thinking patterns, our default responses, our unconscious biases, or the way we actually come across to others. We live inside our own perspective so completely that we mistake it for objective reality. We think we know ourselves, but we're often the last to recognize our most obvious traits.

Why We Can't See Ourselves Clearly

The Fish-in-Water Effect

A fish doesn't know it's wet because water is its entire reality. Similarly, we don't recognize our own patterns because we're swimming in them constantly. Your default way of thinking feels normal to you precisely because it's yours. The salesperson doesn't realize they interrupt prospects because that's how they've always communicated. The perfectionist doesn't see their paralysis because they experience it as "being thorough." The conflict-avoider doesn't recognize their pattern because it feels like "keeping the peace."

The Inside-Out Problem

We experience ourselves from the inside, through our intentions, our internal narrative, and our private motivations. But others experience us from the outside, through our actions, our words, and our visible behaviors. This creates a fundamental gap. You know why you did something, but others only see what you did. You experience your careful consideration, but others see your delay. You feel your passion, but others observe your intensity.

This inside-out disconnect means feedback often feels unfair or inaccurate. When someone tells you that you seem impatient, your first reaction is usually defense: "But I was being thorough!" You're both right, but you're seeing different sides of the same reality.

The Confirmation Trap

We unconsciously filter information to confirm what we already believe about ourselves. If you see yourself as a good listener, you'll notice the times you let others finish talking and forget the times you interrupted. If you believe you're decisive, you'll remember the quick decisions and minimize the times you procrastinated. We're exceptionally good at collecting evidence that supports our self-image and remarkably blind to contradictory data.

The Systematic Nature of Self-Blindness

Personal Blind Spots

Each of us carries a unique constellation of invisible patterns:

The Competence Paradox: The better you become at something, the more unconscious your competence becomes, making it harder to teach or replicate. Master mechanics can diagnose problems by sound alone but struggle to explain their process to apprentices.

The Assumption Invisible: We make thousands of assumptions daily that feel like facts. The manager who assumes everyone wants detailed feedback because they do. The entrepreneur who assumes others share their risk tolerance. The parent who assumes their child processes information the same way they do.

The Strength Shadow: Our greatest strengths often cast the deepest shadows. The analytical person who doesn't realize they're perceived as cold. The innovative thinker who doesn't see how their constant new ideas exhaust their team. The supportive colleague who doesn't recognize when their helpfulness becomes enabling.

Organizational Blind Spots

Companies suffer from collective versions of the mirror problem:

Culture Invisibility: What feels like "just how we do things here" to insiders often appears as rigid, exclusive, or dysfunctional to outsiders. The startup that prides itself on flexibility doesn't see how its constant pivoting creates employee anxiety.

Customer Assumption: Organizations often mistake their internal perspective for customer reality. The software company that thinks their feature is intuitive because the development team finds it logical. The restaurant that believes their atmosphere is "intimate" while customers experience it as "cramped."

Success Blindness: Success often reinforces the very patterns that might become future weaknesses. The company that grew through aggressive sales tactics doesn't realize when the market shifts toward relationship-building.

The Cost of Living Without Mirrors

Personal Costs

Without clear self-awareness, you repeat patterns that limit your effectiveness:

- Relationships suffer because you can't see how others actually experience you

- Career growth stalls because you're unaware of your impact on colleagues

- Decision-making deteriorates because you don't recognize your biases

- Learning slows because you can't identify your actual development needs

Professional Costs

Organizations without systematic self-awareness face predictable problems:

- Strategy fails because leadership can't see their own assumptions

- Innovation stagnates because teams can't recognize their thinking constraints

- Culture problems persist because the behaviors that create them remain invisible

- Customer relationships deteriorate because the company can't see itself through customer eyes

Building Your Mirror System

Since we can't see ourselves clearly through internal reflection alone, we need external systems—mirrors—that show us what we can't see directly.

Mirror Type 1: Feedback Loops

The 360-Degree View: Actively seek input from people above, below, and beside you in various contexts. But don't just collect feedback—create specific questions that reveal blind spots. Instead of asking "How am I doing?" ask "When do you notice me at my least effective?" or "What do I do that I probably don't realize I'm doing?"

The Pattern Interview: Periodically ask trusted colleagues: "What patterns do you notice in my behavior that I might not see?" This isn't about performance evaluation, it's about pattern recognition.

The Impact Audit: Regularly check the gap between your intentions and your impact. After important interactions, ask: "What did you take away from our conversation?" or "How did that land with you?"

Mirror Type 2: External Observers

The Trusted Skeptic: Cultivate relationships with people who will tell you what you need to hear rather than what you want to hear. These should be people who care about your success enough to risk temporary discomfort.

The Naive Questioner: Sometimes the most valuable mirrors are people unfamiliar with your context who ask innocent questions that reveal hidden assumptions. The new employee who asks "Why do we do it this way?" often spots things veterans can't see.

The Customer Voice: Your customers see your business differently than you do. Create systematic ways to hear their unfiltered perspective, not just their polite responses to surveys.

Mirror Type 3: Data and Systems

Behavioral Tracking: What you measure, you can see. Track patterns in your email response time, meeting effectiveness, decision-making speed, or whatever matters most to your role.

The Video Reality Check: Record yourself in action—presenting, leading meetings, or having important conversations. The gap between how you think you come across and what you actually see can be revelatory.

The Decision Journal: Keep track of your predictions and reasoning. Review them later to identify patterns in your thinking that you can't see in the moment.

Mirror Type 4: Structured Reflection

The Red Team Exercise: Regularly argue against your own position. What would a smart critic say about your approach? What assumptions would they challenge?

The Outsider Test: Ask yourself: "If someone else made this decision with these results, what would I think?" We often judge ourselves by our intentions but others by their results.

The Time-Delayed Review: What seemed obvious six months ago that you now see differently? This reveals how your blind spots shift over time.

The Mirror Maintenance Problem

Building mirrors isn't enough—you have to use them consistently and resist the natural tendency to avoid uncomfortable reflections.

Creating Safe Feedback Environments

People won't hold up mirrors if they fear punishment for what they reflect. You must demonstrate that you value accuracy over ego protection. This means thanking people for difficult feedback, asking follow-up questions instead of defending, and showing that you act on what you learn.

Distinguishing Signal from Noise

Not all feedback is equally valuable. Learn to distinguish between one person's opinion and patterns multiple people notice. Look for feedback that explains things you couldn't understand about your results or relationships.

The Calibration Challenge

Your mirrors need regular calibration. Are your feedback sources diverse enough? Are you asking the right questions? Are you creating conditions where people can be honest with you?

Advanced Mirror Techniques

The Assumption Archaeology

Regularly dig up your buried assumptions by asking: "What would have to be true for this approach to fail?" or "What am I taking for granted that might not be true?"

The Role Reversal

Periodically imagine being on the receiving end of your own behavior. If you were your employee, customer, or family member, what would you wish you would do differently?

The Future History

Write the story of a future failure, working backward to identify the blind spots that contributed to it. This reveals current patterns you can't see directly.

When Mirrors Show Us What We Don't Want to See

The hardest part of the mirror problem isn't building the systems—it's accepting what they reveal. We often resist mirrors that show us unflattering truths or challenge our self-image.

The Growth Paradox

The people who most need mirrors are often least likely to seek them out. Confidence and competence can create a false sense of clarity. The most successful people sometimes have the largest blind spots because their success validates their approach, making them less likely to question it.

Working Through Mirror Shock

When mirrors reveal uncomfortable truths, the natural response is to blame the mirror. "They don't understand my situation." "They're not seeing the full picture." Sometimes this is true, but often it's our defense mechanism protecting us from growth.

The key is to sit with discomfort long enough to extract the insight without immediately dismissing it or taking it as a complete condemnation of your character.

The Compound Effect of Clarity

Self-awareness isn't just nice to have—it's a competitive advantage that compounds over time. People who see themselves clearly make better decisions, build stronger relationships, and adapt more quickly to change.

Organizations with systematic self-awareness avoid predictable pitfalls, spot opportunities others miss, and create cultures where problems surface early instead of festering in blind spots.

Your Mirror Strategy

Here's how to start building your personal mirror system:

This Week: Ask three people who see you in different contexts one specific question about a pattern they notice in your behavior. Don't defend or explain—just listen and say thank you.

This Month: Set up one systematic feedback loop—a monthly check-in with a colleague, a quarterly customer conversation, or a regular team retrospective focused on your leadership impact.

This Quarter: Create a data tracking system for one important aspect of your performance that you currently judge only by feeling or intention.

This Year: Build relationships with people who care enough about your success to tell you difficult truths and skilled enough to help you see what you're missing.

The Mirror Paradox

Here's the deepest truth about the mirror problem: the people who most readily seek mirrors are often those who need them least. They already have some self-awareness, which makes them more open to feedback. Meanwhile, those with the largest blind spots often resist mirrors most strongly, precisely because they can't see their need for outside perspective.

But here's what changes everything: mirrors aren't just about seeing problems. They're about seeing potential. They show you not just what's wrong, but what's possible. They reveal strengths you didn't know you had and capabilities you never recognized.

The nose on your face isn't just a physical feature you can't see directly, it's a metaphor for all the obvious things about you that could become your greatest assets if you could only see them clearly enough to develop them intentionally.

Your next breakthrough isn't hidden in some distant opportunity. It's probably sitting right there in your blind spot, as obvious as the nose on your face, waiting for the right mirror to reveal it.

The question isn't whether you have blind spots. Everyone does. The question is whether you'll build the mirror systems to see them before they become limitations that define what you can't achieve.

After all, you can't fix what you can't see. But once you can see it, you can transform it.