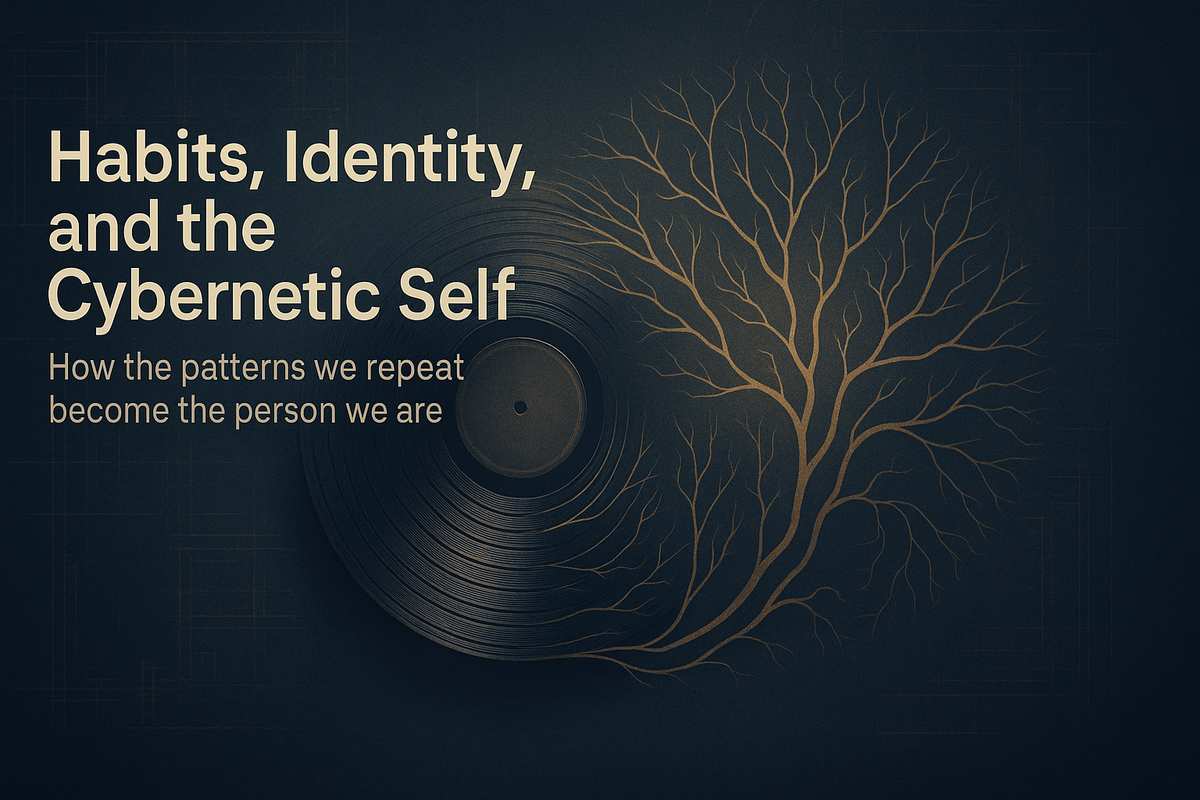

Habits, Identity, and the Cybernetic Self

We wear our habits as surely as we wear our skin. Understanding the connection between identity and behavior is the key to lasting change.

"Man is a creature of habit. You are what you habitually do. Change your habits, and you change yourself." ~ Maxwell Maltz, Psycho-Cybernetics

The Etymology of Habit

The word "habit" carries its history in its very structure. Derived from the Latin habitus, meaning "condition" or "appearance," and habere, meaning "to have" or "to hold," the word originally referred to one's outward bearing or dress. A monk's habit was literally the clothing that identified their state of being. Over time, the meaning shifted inward, from the garments we wear to the patterns we embody, from external costume to internal constitution.

This linguistic evolution mirrors a profound truth: our habits are the clothes we cannot remove. They are what we "have" and what "holds" us. Unlike a monk's robe that can be hung on a hook at day's end, our behavioral habits travel with us everywhere, invisible yet omnipresent, shaping every interaction and outcome.

The Romans understood something essential when they connected clothing to conduct. Both are chosen repeatedly until they cease to feel like choices at all. Both can be changed, though not without deliberate effort. The etymology whispers what neuroscience now confirms: we wear our habits as surely as we wear our skin.

The Cybernetic Self

In 1960, plastic surgeon Maxwell Maltz published Psycho-Cybernetics, revolutionizing our understanding of self-image and behavior change. Maltz had observed something peculiar: when he corrected a physical deformity, some patients immediately adjusted their self-concept and behavior, while others continued to act as if the deformity still existed. The nose was different, but the person wearing it remained the same.

This led Maltz to a profound insight: we are servo-mechanisms, self-regulating systems that operate based on our internal image of who we are. Like a thermostat maintaining a set temperature, we unconsciously adjust our behavior to align with our self-image. Our habits are the automatic adjustments our internal guidance system makes to keep us consistent with who we believe ourselves to be.

The cybernetic principle is simple but transformative: you cannot consistently perform in a way that is inconsistent with your self-image. If you see yourself as someone who is always late, you will unconsciously sabotage efforts to arrive on time. If you see yourself as an unhealthy person, healthy habits will feel foreign, requiring constant willpower because they contradict your internal programming.

This is why New Year's resolutions fail with such predictable regularity. We try to change the habit without changing the self-image that generates the habit. The system, doing what systems do, brings us back to equilibrium, back to the familiar pattern that matches who we believe ourselves to be.

The 21-Day Myth

Maltz observed that his patients seemed to take about 21 days to adjust to their new faces. This has been distorted into the popular claim that it takes 21 days to form a habit. Research by Phillippa Lally at University College London found that habit formation actually takes an average of 66 days, with significant variation. Some habits formed in 18 days, others took more than 250 days.

But Maltz's deeper insight wasn't about the timeline—it was about the mechanism. The 21 days wasn't just about repetition creating neural pathways. It was about the time needed for the self-image to update, for the internal thermostat to recalibrate, for the cybernetic system to accept new data about who this person is.

This explains why some behavior changes stick immediately while others remain perpetually difficult. When a change aligns with your self-image, it integrates effortlessly. When it contradicts your self-image, it requires either superhuman willpower or a fundamental shift in how you see yourself.

The Groove in the Record

Habits function like grooves in a vinyl record. The first time the needle passes over the surface, it makes a slight impression. The thousandth time, the needle falls into the groove automatically. The music plays itself.

But here's what most discussions of habit formation miss: the groove isn't just in your brain. It's in your identity. Each time you follow through on a commitment to yourself, you're etching into your self-image the identity of someone who keeps commitments. Each time you break a promise to yourself, you're reinforcing the identity of someone whose intentions and actions don't align.

This is why the concept of "breaking" a bad habit is misleading. You don't break a groove. You create a new one. You build a new neural pathway that becomes deeper, more traveled, more automatic than the old. And critically, you don't just change what you do. You change who you are.

The Invisible Architecture

We live in houses built by our habits. The daily routines, the automatic responses, the unconscious patterns that fill our days are the walls, floors, and ceilings of our lived experience. Most of us inherit this architecture, accepting the house as given rather than recognizing we are both architect and builder.

The power of this architecture lies in its invisibility. We think we're making choices when we're actually running programs. We believe we're deciding when we're actually defaulting. The habit has become the habitat, and we're so immersed in it we can't see it.

This invisibility is both the problem and the opportunity. You cannot change what you cannot see. But once you see it, change becomes possible. The first step in transforming your habits isn't willpower or motivation. It's awareness—noticing the automatic pattern, catching yourself in the act of being who you've always been.

Identity-Based Habits

James Clear, in his book Atomic Habits, built on insights from Psycho-Cybernetics to introduce the concept of identity-based habits. Instead of focusing on what you want to achieve (outcome-based) or what you want to do (process-based), focus on who you want to become (identity-based).

"I want to lose 20 pounds" is outcome-based. "I want to go to the gym three times a week" is process-based. "I want to become the type of person who takes care of their body" is identity-based. The first two are external goals. The third is an internal transformation.

Identity-based habits work because they leverage the cybernetic principle. When you change how you see yourself, your servo-mechanism adjusts automatically. A person who sees themselves as a reader doesn't need to force themselves to read. The habit aligns with the identity, and the identity generates the habit.

But here's the crucial insight: identity isn't something you're born with. It's something you build through action. Every action you take is a vote for the type of person you wish to become. Every time you write a single sentence, you're voting for "writer." The identity emerges from the accumulation of evidence.

This creates a powerful positive feedback loop: behavior shapes identity, and identity shapes behavior. The groove deepens with each pass of the needle, and the music becomes more automatic, more natural, more yours.

Why Change Doesn't Stick

Understanding the cybernetic nature of self explains one of the most frustrating phenomena in behavior change: you make progress, start to change, begin to see results, and then mysteriously self-sabotage, returning to your starting point as if pulled by an invisible rubber band.

This isn't weakness. It's your internal servo-mechanism maintaining consistency with your self-image. When your behavior gets too far from your identity, the system corrects. If you see yourself as someone who weighs 200 pounds, losing 30 pounds creates dissonance. The system finds ways to return you to the familiar setting.

The solution isn't to fight the thermostat. It's to reset it. This requires working on two levels simultaneously: changing the behavior and changing the self-image. The behavior provides evidence for the new identity, and the new identity makes the behavior feel natural rather than forced.

This is why small, consistent actions are more powerful than dramatic gestures. The person who writes one paragraph every day is changing their identity more effectively than the person who writes 50 pages once and then stops for months.

The Practice of Becoming

If habits are the architecture of self, then building better habits is the practice of becoming—becoming more fully who you choose to be rather than who circumstance has made you.

This practice begins with a simple question: Who do I want to become? Once you have that vision, you can ask: What would that person do? Would they hit snooze or get up with the alarm? Would they scroll social media or read? Each choice is a vote. Each action is evidence. Each repetition is a groove that becomes deeper, more automatic, more you.

The beauty of this approach is that you don't need to be that person yet. You just need to act like that person. The identity will catch up to the behavior. The self-image will adjust to match the evidence. You become who you are becoming through the simple, repeated practice of acting like them.

The House You Live In

You are living right now in a house built by your habits. This house has been under construction your entire life, though often unconsciously, often following inherited blueprints, often working from habit itself rather than intention.

The revelation of Psycho-Cybernetics is this: you can redesign this house. Not overnight, but genuinely, fundamentally, through the patient, consistent practice of new patterns. The servo-mechanism will adjust. The thermostat will reset. The self-image will update to match the evidence of who you're becoming.

Your habits are not your destiny. They are your sculpture material. And you, whether you've realized it yet or not, are the sculptor. The question isn't whether you're shaping yourself—you're always shaping yourself. The question is whether you're doing it consciously, deliberately, in alignment with who you choose to become.

Start small. Choose one behavior that aligns with who you want to be. Practice it until it becomes automatic. Let it become evidence that updates your self-image. Then choose another. You're building yourself, brick by brick, habit by habit, choice by choice.

The architecture of self is always under construction. The question is: who's holding the blueprint?