Are You an Impostor?

You've built an elaborate job that's holding your own company hostage. You wanted freedom. You built a prison.

"The greatest leader is not necessarily the one who does the greatest things. He is the one who gets the people to do the greatest things." ~Ronald Reagan

The Complaint

I recently came across an article where a CEO was complaining that he couldn't run his company and write the code for his software at the same time.

Read that again.

A CEO, someone ostensibly running a company, was frustrated that he couldn't simultaneously be in the engine room doing the technical work. His complaint wasn't about a temporary crisis requiring all hands on deck. It was about his normal operational reality. He genuinely seemed to believe the problem was insufficient hours in the day, not a fundamental confusion about what his job actually is.

The response that immediately came to mind? Then hire a CEO.

Because if you want to write code, be a developer. If you want to run a company, be a CEO. But you don't get to do both and then complain that it's impossible. You've chosen the wrong chair.

The Ship Without a Captain

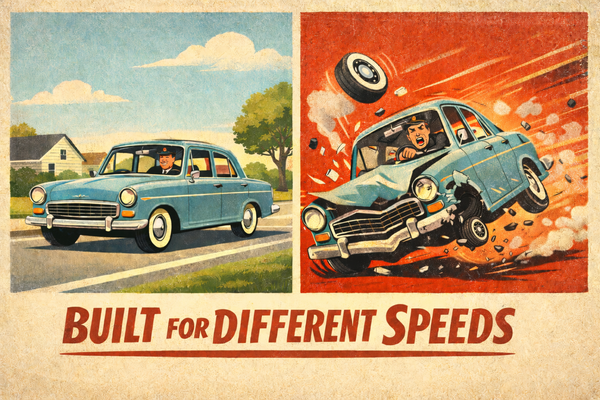

Here's what actually happens when the captain insists on staying in the engine room:

The ship hits the iceberg.

Not might hit. Not could face challenges. Will crash. Because while the captain is below deck perfecting the engines, nobody is on the bridge watching the horizon. Nobody is steering. Nobody is seeing what's coming.

And here's the tragedy: the engines will be running perfectly when they hit.

The code will be elegant. The systems will be optimized. The technical work will be flawless. None of it matters because the ship is going in the wrong direction, or no direction at all, or straight into an obstacle that anyone on the bridge would have seen miles away.

The crew can run the engines. Multiple people on your team can write code, manage systems, execute technical work. But they cannot captain the ship. That job, watching the horizon, making strategic decisions, seeing around corners, steering toward opportunity and away from disaster, that job only the captain can do.

And when the captain abandons the bridge to do work the crew can handle, the ship becomes fundamentally ungovernable.

The Real Problem: The E-Myth Trap

"If your business depends on you, you don't own a business, you have a job. And it's the worst job in the world because you're working for a lunatic!" ~Michael Gerber, The E-Myth Revisited

This CEO isn't alone in his confusion. He's living the fundamental trap that catches most entrepreneurs: you started the business because you're great at the thing.

You're a brilliant developer, so you start a software company. You're an incredible designer, so you launch a design firm. You're a master craftsman, so you open a custom furniture business.

But here's what nobody tells you: being great at the thing doesn't make you great at running a business that does the thing.

Being able to write beautiful code doesn't mean you know how to:

- Read market conditions and spot opportunities

- Build and lead teams

- Make strategic bets about where to invest resources

- Navigate competitive threats

- Understand what customers actually need versus what they say they want

"The customer rarely buys what the company thinks it's selling," Peter Drucker observed. But you only know what the customer is actually buying if you're up on the bridge with the telescope, not down in the engine room with a wrench.

The transition from working IN the business to working ON the business isn't just a skill upgrade. It's a complete identity shift. And most entrepreneurs resist it violently because:

Identity: "I'm a developer" feels true and grounded. "I'm a CEO" feels like playing dress-up, like pretending to be something you're not.

Comfort: The engine room is familiar territory. You know you're good there. The bridge is unfamiliar, ambiguous, sometimes terrifying. You're making decisions without immediate feedback, placing long-term bets with uncertain outcomes.

Validation: In the engine room, you get instant feedback. The code compiles or it doesn't. The system works or it breaks. On the bridge, you're making strategic decisions whose outcomes won't be clear for months or years. The feedback loop is agonizingly slow.

So entrepreneurs retreat to what they know. They stay in the engine room where they feel competent, where the work is concrete and familiar, where they can see immediate results. They tell themselves they're being hands-on, staying connected to the work, maintaining quality standards.

What they're actually doing is abandoning their post.

The Brutal Truth

Here's the line that nobody wants to hear:

You've built an elaborate job that's holding your own company hostage.

The entrepreneur thinks: "I'm working 80 hours a week building my dream."

The reality: "I'm working 80 hours a week in a prison I designed myself."

The hostage situation runs both ways:

You're holding the company hostage because nothing moves without you. Every decision must flow through you. Every technical problem requires your personal attention. Every client issue needs your involvement. The business can't function unless you're present and actively working.

The company is holding you hostage because you can't leave. You can't take a vacation. You can't get sick. You can't focus on strategy because operations demand constant attention. You're trapped in the execution layer, unable to rise to the strategic level where you could actually create disproportionate value.

You wanted freedom. You built a prison.

And here's what makes this particularly brutal: every hour you spend being irreplaceable makes you more trapped, not less. Every system you build around yourself, every process that requires your personal touch, every decision that must flow through you, you think you're building value. You're building bars.

The CEO who can't stop writing code isn't valuable because he can code. He's trapped because he never taught anyone else how. The baker who insists on making every cake isn't maintaining quality standards. She's preventing growth. The consultant who won't delegate client relationships isn't being thorough. He's creating a business that dies the moment he does.

What looks like dedication is actually dysfunction. What feels like being indispensable is actually being stuck.

Playing Company

At least the CEO who can't leave the engine room is being honest about his confusion. He has a real company with real employees, and he's genuinely struggling with which job he should be doing.

But there's another trap that's even more insidious: the entrepreneur playing company.

You know the type. One person with five email addresses. sales@company.com. support@company.com. partnerships@company.com. operations@company.com. All going to the same inbox. Fake department names. Phantom team members mentioned in emails. "I'll have my team look into that." "Our operations department will get back to you." "Let me check with our technical staff."

It's all theater. Behind the curtain, it's one person frantically switching hats, maintaining the elaborate fiction that they're a real company with real departments and real people.

Why Do They Do This?

Fear, mostly. Fear that being small means being illegitimate. Fear that clients won't trust a solo operator with important work. Fear that admitting you're one person means you can't win big deals or charge real prices.

So they build the illusion. They create the appearance of scale where none exists. They're playing company the way children play doctor, going through the motions, using the props, speaking the language, but not actually doing the thing.

There is absolutely no good reason to LARP. The illusion always crumbles, and when it does, you've destroyed the one thing you can't rebuild: trust.

The Cost of the Theater

Here's what nobody tells you about maintaining this illusion: it's exhausting.

Every email requires you to think about which fake persona should send it. Every client interaction requires you to remember your lies. Every meeting demands you maintain the fiction. You're not building a business, you're producing a one-person show with a cast of invented characters.

And here's the brutal part: every hour you spend maintaining the theater is an hour you're NOT spending actually building something real.

You could be developing systems. Training actual people. Creating real capacity. Instead, you're managing email addresses and inventing excuses for why "the team" is slow to respond.

The Noose Tightens

The longer you maintain the illusion, the harder it becomes to escape:

You can't hire real people because you've already created fake ones. How do you introduce an actual operations manager when clients think they've been talking to your operations department for months?

You can't be honest about your capacity because you've been lying about it. You've promised things that require a team to deliver, and you're one person.

You can't raise your prices to reflect your actual boutique expertise because you're pretending to be a mid-sized firm with mid-sized firm overhead.

The theater becomes its own prison. You're trapped maintaining a lie that prevents you from building the truth.

And when the truth inevitably comes out, because it always does, you've destroyed your credibility completely. The client who discovers they've been emailing the same person through five different addresses doesn't think "clever marketing strategy." They think "liar." They wonder what else you've been dishonest about. Your pricing. Your capabilities. Your timelines. Your results.

You can recover from being small. You can't recover from being a fraud. Once people figure out the emperor has no clothes, the vandals destroy the empire.

The Honest Alternative

Here's what's insane about all this: being small is completely legitimate.

Boutique firms command premium prices BECAUSE they're small. Because you get the principal, not an account manager. Because the person who answers the email is the person doing the work. Because there's no bureaucracy, no handoffs, no telephone game.

Some of the most successful consultants, designers, developers, and strategists in the world are solo operators who've never pretended to be anything else. They charge top dollar precisely because clients know they're getting direct access to the expert, not "the team."

But you have to own what you are. You have to be honest about your capacity. You have to build your business model around being excellent at what you do, not around appearing bigger than you are.

The Common Thread

Whether you're playing company with five email addresses or playing CEO while staying in the engine room, the fundamental problem is the same:

You're lying about what job you're actually doing.

The five-email entrepreneur is lying to clients about who they are. The engine-room CEO is lying to himself about what his job requires. Both are maintaining fictions that prevent them from building something real.

The iceberg doesn't care about your elaborate email system. It doesn't care about your fake departments. It doesn't care whether you're honest about being a solo operator or pretending to run a team.

The iceberg only cares that nobody's actually watching where the ship is going.

The Law of Business Physics

You cannot scale a business that requires you to be in the engine room.

Period.

This isn't advice. It's not a best practice. It's not something you can work around with enough hustle or talent or eighteen-hour days. It's physics.

A business scales to the limit of its constraints. If the constraint is "only the founder can do X," then the business scales to exactly the capacity of one person doing X. No amount of working harder, staying later, or "grinding" changes this fundamental equation.

The entrepreneur in the engine room is like someone trying to lift themselves by their own bootstraps. The effort is real. The intention is sincere. The physics don't care. It's mathematically impossible.

And here's what makes this law particularly unforgiving: the longer you wait to fix this structural problem, the harder it becomes to solve.

At 5 employees, building systems that work without you is straightforward. You can document processes, train people, create redundancy relatively easily.

At 20 employees, it's disruptive but doable. You'll need to restructure some things, possibly hurt some feelings, definitely step on some toes. But it's manageable.

At 50 employees, you're doing organizational surgery. Systems are entrenched. Dependencies run deep. People have built their roles around your involvement. Changing this requires careful planning and significant pain.

At 100 employees, you're essentially stuck. The organization has calcified around your presence in the engine room. Everyone knows it. Your team knows it. Your competitors know it. And worst of all, potential acquirers or investors know it. You've built a company that's fundamentally un-scalable and possibly unsellable.

The iceberg doesn't care how hard you're working. It doesn't care how elegant your code is. It doesn't care how many hours you're putting in.

The iceberg only cares that nobody was watching where the ship was going.

The Continuity Test

Here's the diagnostic question that reveals everything:

Can your business run for a week without you?

Not run perfectly. Not run at peak efficiency. Just run. Can operations continue? Can customers be served? Can decisions be made? Can problems be solved?

If the answer is no, you don't have a business. You have an elaborate job that requires your constant presence.

Now extend the timeline: What about two weeks? A month? Three months?

The point where your business starts to fall apart is the point where you've failed to build the systems and develop the people necessary for scale. It's the exact measure of how much you're holding your own company hostage.

This isn't theoretical. It's about building resilience into your business model from day one. Because if you can't take a vacation, you also can't:

- Focus on strategic planning when operations demand attention

- Pursue new opportunities because current operations consume all your time

- Respond to competitive threats because you're buried in execution

- Scale beyond your personal capacity to do the work

- Sell the business because it's too dependent on you

- Get sick without everything grinding to a halt

A continuity plan isn't pessimistic. It's strategic. It's the foundation of everything that comes next.

Planning From Day One

The entrepreneurs who successfully scale understand something crucial: you don't wait until the ship is big enough to need a captain. You build the ship knowing you'll need to captain it.

This is what separates businesses that scale from businesses that stay trapped:

The ones who crash build everything around themselves as the indispensable engine room worker. Every system requires them. Every decision flows through them. Every process depends on their personal involvement. They've built a ship that can only function if the captain never leaves the engine room. They're trapped before they even realize there's a problem.

The ones who scale build knowing their job will change. From day one, they're creating systems that work without them. They're hiring people and actually empowering them. They're documenting processes not because they need it today, but because they're building a ship that can be captained tomorrow. They're planning for the transition before it becomes a crisis.

What does planning from day one actually look like?

The Three Stages of Growth

Stage One: The Rowboat

In the beginning, you are everything. Captain, crew, engine room worker, navigator, cook. This is appropriate. This is necessary. When you're building something from nothing, you need to be in the engine room because there is no bridge yet. There's barely a boat.

But even here, even at the rowboat stage, you should be thinking about systems. How you do what you do. Why it works. What could be taught to someone else. You're creating the DNA of the future organization, even when that future organization is just you and maybe one other person.

The mistake people make at this stage is thinking it will always be this way. "I'll just keep doing what I'm doing, but more of it." That's not growth. That's just running faster on the same treadmill.

Stage Two: The Growing Vessel

Now you're hiring people. You have actual crew members. And this is where the crucial choice happens, the fork in the road that determines everything that follows:

Are you building systems that need you, or systems that work without you?

Are you training people to replace you in specific functions, or training them to be dependent on you for decisions?

Are you documenting how things work so others can learn, or keeping the knowledge in your head where it makes you indispensable?

Are you building redundancy into critical roles, or creating single points of failure?

This is the stage where most entrepreneurs make the fatal mistake. They hire people, but they hire them to do tasks while they maintain control of the thinking. They build a larger engine room but keep themselves at the center of every decision. They're still working IN the business, just with more people around them doing pieces of what they used to do alone.

The right move at this stage? Start building the bridge even though you're not ready to stand on it full-time yet. Create systems. Document processes. Train people to make decisions. Build slack into the organization so it can handle problems without you.

Every hour you spend in the engine room, ask yourself: "Could I teach someone else to do this? Should I be doing this at all? What would need to be true for this to work without me?"

Stage Three: The Ship

At this stage, you must be on the bridge. Not occasionally. Not when you can spare time from the engine room. Always.

If you built the ship correctly in Stage Two, this transition is natural. The engine room runs without you because you spent years building it to run without you. The crew knows their jobs because you trained them to think, not just execute. The systems work because you documented them. The organization has resilience because you built redundancy.

You can stand on the bridge and actually captain because you're not the only person who knows how the engines work.

If you built it wrong, if you made yourself indispensable in Stage Two, then Stage Three is a crisis. You need to be on the bridge, but the ship can't function without you in the engine room. You're trapped. The business is trapped. Growth becomes impossible.

This is where that CEO finds himself. He built a ship that requires him to be in the engine room, but the ship is now big enough to need a captain on the bridge. He can't do both. And because he never planned for this transition, he has no good options.

What Planning Actually Looks Like

From day one, even when you're doing everything yourself:

Document everything. Not someday. Now. How you do what you do. Why it works. What the exceptions are. Write it down like you're teaching someone else, because eventually you will be. The time to document the process is while you're doing it, not when you're desperately trying to hand it off to someone six months from now.

Build systems, not dependencies. Every process you create should be designed to work without you. Yes, you're doing it now. But design it so someone else could do it with the documentation you're creating. Build checklists. Create templates. Establish standards. Make it repeatable.

Train people to think, not just execute. When you hire someone, don't just give them tasks. Teach them the principles behind the tasks. Explain why you make certain decisions. Share your decision-making framework. The goal isn't to clone yourself, it's to create people who can solve problems you haven't anticipated yet.

Create redundancy in critical functions. If only one person knows how to do something critical, that's a bomb waiting to go off. What happens when they quit? Get sick? Go on vacation? Build overlap. Cross-train. Make sure critical knowledge lives in multiple heads and in documented systems, not in a single person.

Test your systems regularly. Can the business run without you for a day? A week? Try it. Not someday when you feel ready. Now. Take a Friday off. Don't check email. See what breaks. Then fix those things. Then try a longer period. Keep testing and fixing until the answer is yes.

Hire for your replacement, not your assistant. When you bring people in, don't hire people to do tasks you don't want to do. Hire people who can eventually do your job better than you can. Hire the person who will run the engine room so well you'll never need to go back down there.

The Captain's Real Job

So what does the captain actually do if they're not in the engine room?

The captain watches for icebergs.

The captain sees what's coming before it arrives. Market shifts. Competitive threats. Opportunities that will pass by if nobody's watching. Customer needs evolving in ways the engine room can't detect. Regulatory changes. Technology disruptions. Strategic partnerships. Talent that needs to be hired. Problems brewing that will become crises if unaddressed.

The captain makes strategic decisions about where the ship is going. Not the day-to-day operational decisions, those should be handled by the crew. But the big decisions that determine whether you're sailing toward opportunity or toward disaster.

The captain builds the next ship. Because the ship you're on today won't be the ship you need tomorrow. Markets change. Competitors adapt. Customer needs evolve. The captain is always thinking one ship ahead, planning for what comes next while the crew runs what exists today.

The captain trusts the crew. This might be the hardest part. Trusting that the engines will run without you hovering. Trusting that people will make good decisions if you've trained them well. Trusting that problems will be solved even if you're not personally solving them.

The captain creates clarity. Where are we going? Why does it matter? What does success look like? The crew can't execute a vision they don't understand, and they can't understand a vision that's locked inside the captain's head because the captain is too busy in the engine room to communicate it.

None of this happens if you're writing code. None of this happens if you're doing the technical work. None of this happens if you're in the engine room.

These aren't things you do when you have spare time. These are the things that determine whether your business survives, let alone thrives.

The Choice

Here's what it comes down to:

If you want to write code, be a developer. That's a completely valid choice. There's honor and satisfaction in being exceptional at craft. You can build a great career, maybe even a small boutique firm, staying in the engine room. Some of the best developers in the world have never managed anyone and never wanted to.

But if you want to build a company, a real company that scales, that creates jobs, that serves customers at a level beyond what you personally can deliver, then you need to be on the bridge.

And you can't do both.

The CEO who's frustrated he can't simultaneously run the company and write the code has failed to make this choice. He wants the title and authority of captain while maintaining the comfort and identity of the engine room worker. He wants to scale while remaining indispensable. He wants to build a company while keeping the work he loves.

The universe doesn't care what you want. The physics remain the same.

You can be the best person in the engine room, or you can be the person on the bridge making sure the ship doesn't hit the iceberg. Pick one.

If you pick the engine room, hire a CEO. Or accept that you're running a boutique operation that will never scale beyond your personal capacity. Both are fine choices as long as you're honest about what you're choosing.

If you pick the bridge, get out of the engine room. Train people. Build systems. Document everything. Create redundancy. Test your continuity plan. Make yourself unnecessary to daily operations so you can be essential to long-term strategy.

But stop pretending you can do both and then complaining that it's hard.

The Iceberg Is Still There

While you're reading this, there's an iceberg out there with your company's name on it.

It might be a competitor you haven't noticed. A market shift you're too busy to see. A technology disruption brewing while you're perfecting the current systems. A key employee planning to leave. A customer need evolving in ways you're missing. A strategic opportunity that will pass by because nobody's watching the horizon.

The iceberg doesn't care that you're working hard. It doesn't care that you're good at what you do. It doesn't care that your code is elegant or your systems are optimized.

The iceberg only cares whether there's someone on the bridge.

The question isn't whether the iceberg exists. It always does. The question is whether you'll be on the bridge to see it coming, or in the engine room when you hit it.

Choose wisely. The ship, and everyone on it, is depending on you to choose correctly.